In 1926, the first confirmed crossing of the North Pole was achieved, not by land or sea, but from the air. This historic flight was made by the airship Norge, a dirigible steered by the skilled Italian pilot and airship engineer, Colonel Umberto Nobile. The 16-man expedition, aboard the Norge also included the famed Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen who served as the navigator and expedition leader, and American millionaire explorer Lincoln Ellsworth, who helped finance the expedition.

Amundsen, already celebrated for traversing the Northwest Passage and reaching the South Pole, sought to conquer the North Pole. In 1925, he contacted Nobile to build a specially designed airship for this mission. However, a project of this magnitude required the approval of Benito Mussolini, the leader of Fascist Italy, who granted his consent.

On May 14, 1926, the Norge successfully crossed over the North Pole and continued on to Alaska and then Seattle. Despite the shared glory, media attention often favored the dashing Colonel Nobile over Amundsen, leading to tensions. Filled with pride following the success of the Norge expedition, the Italian authorities enlisted Nobile for another Arctic venture in 1928, this time aboard the airship Italia. The plan was to fly the airship from King’s Bay in Norway to Greenland, then follow the 27th meridian to the North Pole, and onward to North America. Nobile’s mission was meticulously planned and scientifically equipped.

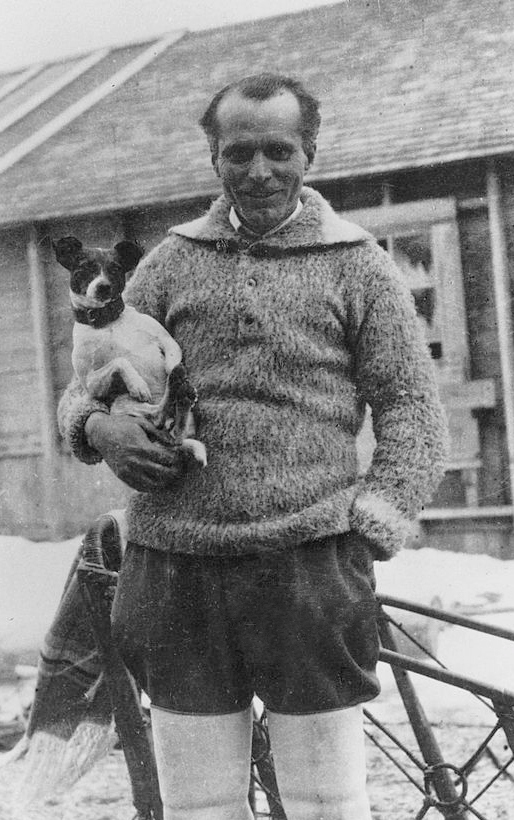

On May 23, 1928, the airship Italia, equipped with scientific instruments, a crew of sixteen, three scientists, survival gear, and Nobile’s dog Titania, took off early in the morning. Their journey began with a successful flight to Cape Bridgman on Greenland’s north-east coast, where they arrived on a sunny afternoon by 5:30 p.m. Then they turned north towards the Pole aided by a strong tailwind. Just after midnight on May 24, they circled the North Pole, dropping Italian and Milanese flags and a heavy wooden cross from the Pope.

The initial triumph soon gave way to a critical decision point. A disagreement arose over the next course of action: Swedish meteorologist Malgren suggested a return to King’s Bay to continue their exploratory flights, while Nobile wanted to fly to the United States. Malgren’s advice prevailed, and they headed back towards Spitsbergen. At 2:30 am, the return flight began, but quickly turned perilous. Ice began forming on the airship’s envelope and they encountered increasing headwinds and thick clouds.

As the airship struggled for eight hours in clouds, fog, and wind, the controls malfunctioned. Nobile ordered to stop the engines for repairs and allowed the airship to rise above the clouds. As they emerged from the fog at 3609 feet in bright sunshine, they could check their location. However, the sun’s heat, was causing the gas to expand and some of it was being expelled through the automatic valves. To prevent further loss, Nobile ordered his crew to bring the airship to a lower altitude, but the foggy conditions below caused the remaining gas to contract, making the airship heavy and unmanageable.

Tragically, on May 25th at 11 am, the Italia crashed onto the Arctic ice, breaking off the control car and the rear engine gondola. The crash left one crew member dead, nine injured, and six missing, as the detached hull of the airship drifted away, never to be seen again. The Italia had crashed 140 miles northeast of Spitsbergen.

Nobile was also among the nine injured survivors. They pitched a red tent, designed to be seen from afar, and waited for help. Though they managed to send out a distress signal, they were not certain if anyone would receive it. Fortunately, a Russian ham radio operator picked up their S.O.S., but it took an agonizingly long time to organize and dispatch a relief expedition to rescue the Italia crew.

“Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-05738 / Georg Pahl / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE”

Approximately 1,500 people from eight countries were involved in a massive international rescue effort. Despite this, it was weeks after the crash before an Italian rescue plane finally spotted them in their red tent and dropped some supplies. Roald Amundsen, the explorer who had accompanied Nobile on their pioneering flight over the North Pole in 1926, joined the extensive international rescue mission to locate the Italia and its crew. He boarded a French plane as part of the search efforts, but tragically, the aircraft disappeared, and Amundsen’s body was never recovered.

A Swedish two-seater plane later landed on the ice and could only take one person. Nobile, despite his reluctance, was persuaded to leave due to his injuries, a decision that would later haunt him. He was promised that his crew would be rescued immediately after, but the Swedish pilot Lundberg could not fulfill his promise as his returning aircraft crashed by the survivors’ tent.

Nineteen days later, the Soviet icebreaker Krassin finally reached the remaining survivors. By that time, one of them, a Swedish meteorologist, had succumbed to exhaustion, hunger, and frostbite—or so the other survivors claimed. However, skeptics suspected cannibalism.

The survivors had endured forty-five grueling days on the ice. The catastrophe was a major humiliation for the Italian Fascist government. Nobile’s early rescue turned him into a scapegoat. In a rushed court inquiry, led by Air Minister Balbo, Nobile was unjustly blamed and wasn’t even summoned to defend himself. Devastated, he resigned from the Italian Air Force and left Italy in the 1930s, accepting an invitation from the Soviet Union to assist with their airship production. He lived there until the onset of World War II. One of his aims was to return to the crash site to recover the bodies of his missing crew, a goal that remained unfulfilled.

After the war, the report that had blamed Nobile for the 1928 crash was discredited, and he was reinstated in the air force. He resumed teaching at the University of Naples and served as a deputy in the Italian Constituent Assembly in 1946.

However, despite his vindication and achievements, his reputation suffered greatly. It’s worth noting that Nobile had successfully piloted the airship Norge and had reached the North Pole in 1926, showcasing his remarkable skill in navigating the treacherous Arctic terrain. Additionally, his airship Italia also had reached the North Pole, but the tragic accident on the return journey tarnished his legacy, resulting in significant damage to his reputation.

Nobile’s story remains a poignant chapter in the history of both polar exploration and Lighter-than-Air (LTA) aviation, illustrating the triumphs and tribulations of early 20th-century adventurers. Operating LTA crafts is exceptionally challenging, as pilots must contend with harsh and dangerous natural elements that can easily render the craft useless. Despite the adversity and controversy, Nobile’s legacy endures as a testament to the bravery and resilience of those who pushed the boundaries of human exploration.

Featured Image Attribution:

“Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-05738 / Georg Pahl / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE”