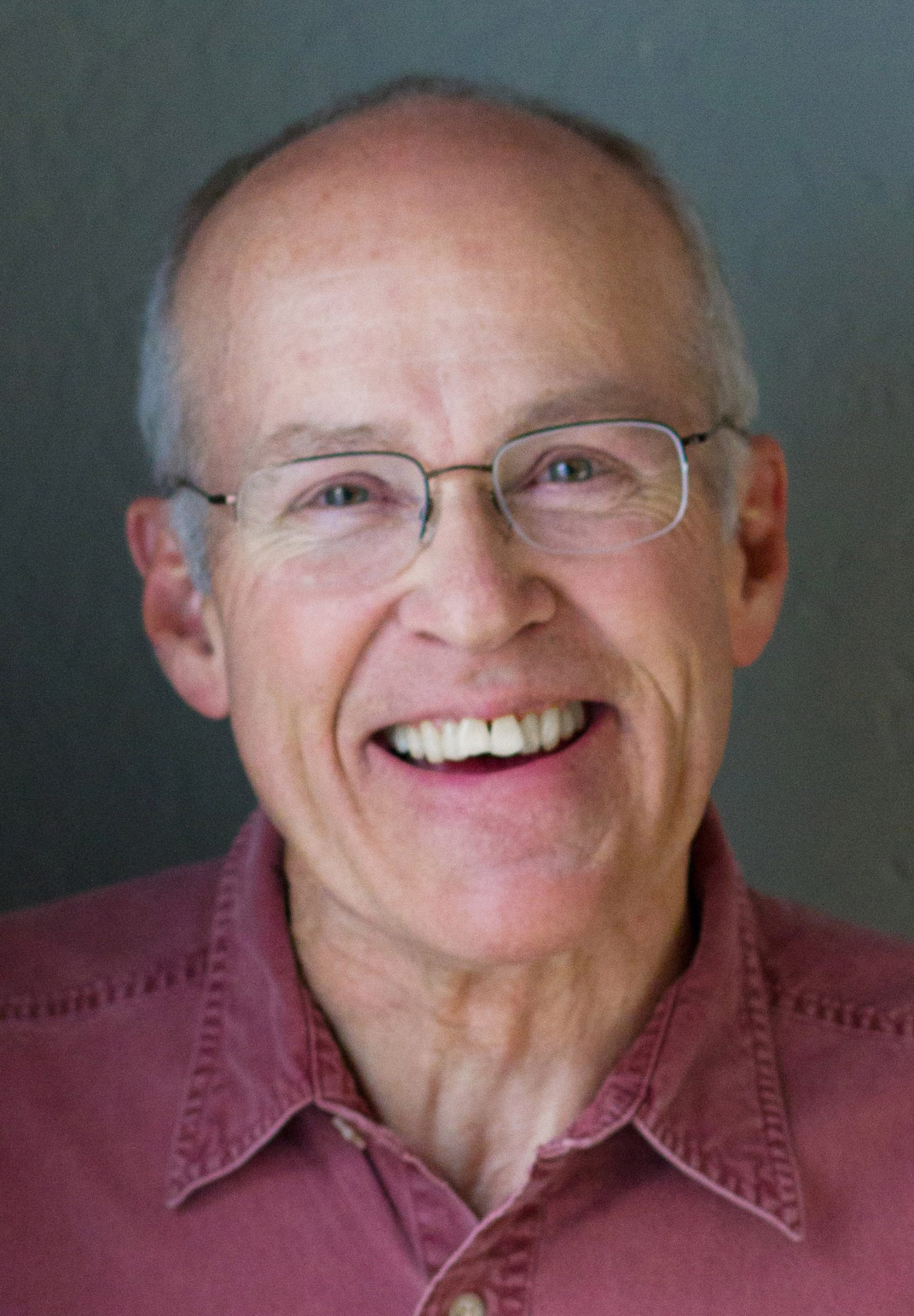

Bruce Comstock has spent his life reaching new heights flying balloons. In 1995, he flew a hot-air balloon to 30,820 feet, near the top of the troposphere, where temperatures drop to around minus 70°F. He has earned multiple world records in altitude, distance, and duration, with recognition in U.S. and international ballooning halls of fame.

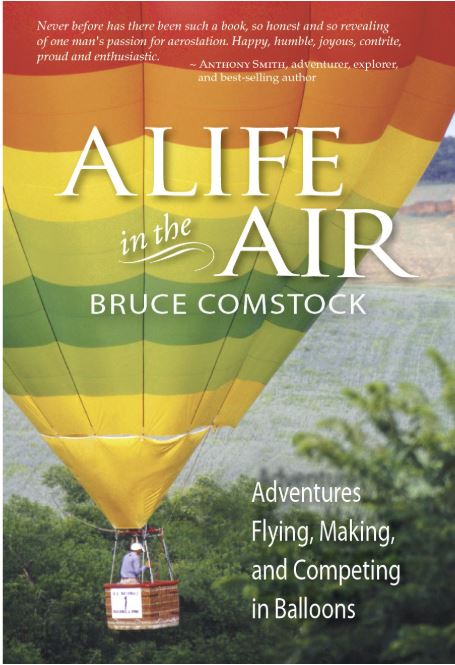

Beyond his flights, Bruce has driven innovation in ballooning, contributing to round-the-world attempts and developing technologies like autopilots and altitude alarms. His book, A Life in the Air, is a compelling chronicle of innovation, passion, and the indomitable spirit of flight, detailing his record-breaking adventures and the behind-the-scenes challenges that shaped them.

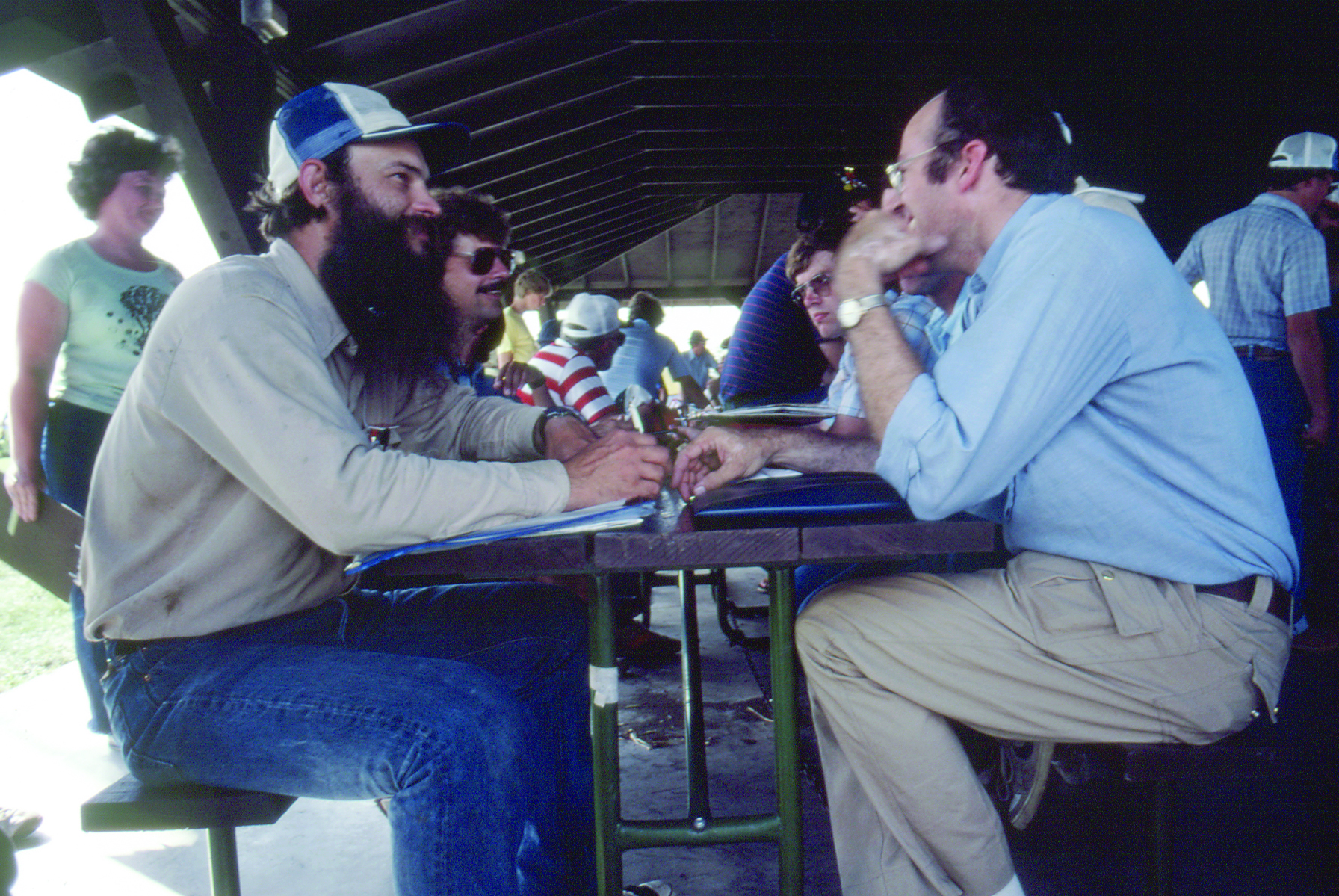

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this article are courtesy of Bruce Comstock.

In an interview with Sitara Maruf, Bruce reflected on key moments from his extraordinary journey. Excerpts from their conversation are below, with more insights to follow in a forthcoming project.

Sitara Maruf: Let’s start with one of your remarkable achievements—your 1995 hot air balloon flight to 30,820 feet. How did you prepare for such a high-altitude flight?

Bruce Comstock: That altitude is above about 70% of the atmosphere, so oxygen levels are critically low. If your breathing oxygen system fails, you could lose consciousness in about 30 seconds and would be fatal if not addressed immediately. To prepare, I borrowed a military-grade oxygen mask and regulator from a friend who had flown F-4 jets in the Marines. I also carried a backup oxygen system, a simpler setup that could sustain me in case of failure.

Another challenge was modifying the balloon burner. Burners typically don’t work well at 30,000 feet because the flame lifts off the burner base due to the thin air and then goes out, releasing unburned propane. To solve this, I modified the jets and fed supplemental oxygen to the pilot light of one burner. This allowed me to relight the burner if it flamed out.

I was also fortunate to borrow the right size balloon from Cameron Balloons, even though I had recently left the company. It was critical to have the right equipment for reaching that altitude.

Gas balloons are somewhat easier to take to high altitudes because you can use a larger envelope to compensate. With a hot air balloon, you face the additional challenge of high envelope temperatures due to low air density at those altitudes. But that’s balanced by the fact that it’s incredibly cold at 30,000 feet, minus 65 degrees Fahrenheit. However, the envelope temperature was around 250 degrees, creating a temperature differential of about 315 degrees. This unusual difference was enough to generate lift in the thin air, where the density is only 28% of what it is at sea level.

Sitara Maruf: Could you share the purpose for making this flight?

Bruce Comstock: Many people ask why I attempted this flight. The International Aeronautic Federation (FAI) had established a pilot badge system with various levels of achievement—silver, gold, and diamond—based on completing tasks like distance, duration, altitude, and competition accuracy. For the highest diamond level, I had already completed everything except the altitude requirement: a flight to 9,000 meters, or about 29,000 feet.

Since I had already achieved the other requirements, I decided to take on this challenge. I aimed for 30,000 feet instead of 29,000 because it felt like a more significant milestone—a big round number.

During the flight, I encountered burner issues starting around 25,000 feet. The flame kept going out due to the thin air, and I had to adjust the position of the blast valve handle very carefully to keep the burner working. At one point, I removed a glove to make finer adjustments, but the extreme cold caused my hand to go numb. First, it hurt intensely, and then it stopped hurting entirely—a bad sign. I had to stop using that hand to avoid further damage.

Somewhere just over 30,000 feet, I thought, “This is the goal I set.” I was struggling with the burner, and I asked myself, why continue going higher? I had achieved my objective, and the issues with the burner were concerning. I was also spraying unburned propane into the envelope, which I didn’t like.

Sitara Maruf: Balloon pilots generally can’t fly above 18,000 feet because of air traffic control regulations to provide a separation between balloons and other aircraft. Did the Federal Aviation Administration grant permission easily, considering the dangers of high-altitude flights?

Bruce Comstock: That was interesting. I contacted the Air Route Traffic Control Center in Cleveland, which oversees southern Michigan, and was quickly connected to someone managing airspace restrictions. I had also approached my local FAA office beforehand. Those conversations were… interesting. The local office said they couldn’t grant permission and had to “bump it up to Washington.” I immediately thought, “This will take years.” They believed I needed a special permit, but I realized that wasn’t the case. So, I contacted the Air Route Traffic Control Center in Cleveland directly. I explained my plan to take off early, possibly before sunrise, to minimize interference with passenger traffic between Detroit and Chicago. I also assured them I’d only stay at high altitude briefly before descending. He told me, “You have just as much right to be there as the jets do.” That was a relief. (laughs)

Sitara Maruf: At high altitudes, beyond 20,000 feet, how does the thin air affect the ascent and descent of a balloon?

Bruce Comstock: The thin air is actually advantageous in some ways. Air produces drag, which you need to overcome during ascent. At high altitudes, with less air density, the drag is significantly reduced. On descent, the thin air allows the balloon to descend faster without collapsing as much as it would at lower altitudes.

Sitara Maruf: You created an autopilot for Steve Fossett’s Atlantic flight in a Rozière balloon. Could you explain how it works and its role in long-distance ballooning?

Bruce Comstock: After getting involved in ballooning, I realized it was possible to build a device to sense air pressure and keep a balloon level—essentially an autopilot. In the late 1970s, before digital computers, I taught myself to design analog circuits and built a simple autopilot in my basement. It wasn’t highly developed, but it worked. Don Cameron knew about it and told Steve Fossett to contact me when he needed an autopilot for his Atlantic flight.

Steve asked me several times to make one, but I initially declined because of the tight timeline. However, my friend Tim Cole, who was flying with Steve, convinced me to create a basic autopilot as a favor. It was a rudimentary device, and I considered it be something of a “toy.”

This autopilot wasn’t very precise—it drifted 600-800 feet off altitude in a few hours because it only used a rate-of-climb instrument, not a pressure sensor. After the Atlantic flight, I told Steve I could build a more reliable one and suggested making two for redundancy.

Sitara Maruf: Did the autopilot detect bad weather or shifting winds?

Bruce Comstock: No, its sole purpose was to maintain a constant altitude. It used an air pressure sensor and a sensitive electronic rate-of-climb input. If the balloon deviated from the desired altitude, the autopilot adjusted to bring it back. For this, I learned to program a single-board industrial digital computer, which was quite a challenge at the time.

Sitara Maruf: For your Aspen-to-Altoona flight, you used the same Rozière balloon that Steve Fossett flew for his successful Atlantic crossing. Flying at night over the Colorado mountains, with peaks reaching 14,000 feet, must have been daunting. How does mountainous terrain affect the balloon and wind patterns?

Bruce Comstock: I had no prior experience flying over mountains, but I remembered a paper by an Austrian balloonist. He warned that if winds at the elevation of the terrain reach 30 knots or more, mountain waves can form. These waves occur when air is forced up by ridges, overshoots, and then oscillates in waves. Flying in those conditions is untenable for a balloon. For this flight, I carefully checked wind forecasts and ensured the conditions were safe before takeoff.

Sitara Maruf: Let’s move on to Steve Fossett’s solo Pacific flight. You worked as co-launch director. What challenges did you face?

Bruce Comstock: Having Nick Saum as a co-director made a big difference. We could share responsibilities and discuss decisions. Nick and I worked on three of Steve’s launches: the Pacific flight, and two of his round-the-world attempts, the first one from the Stratobowl, and the second one from St. Louis.

We didn’t come in at the beginning of the projects, so we often had to work with equipment and decisions already made by Steve and his team. That was frustrating at times, but our job was to ensure everything was ready and functioning, and to oversee the balloon inflation—a complex process.

The Pacific flight required Steve to fly at very high altitudes, where it gets extremely cold. Nick and I realized the propane wouldn’t vaporize at those temperatures, causing the burner to fail. From prior experiments, I knew ethane could work in cold conditions. It burns similarly to propane and mixes well with it.

Nick, a PhD from the Colorado School of Mines, was incredibly sharp when it came to science. I also have a good technical background, so we worked well together. At dinner one evening, I explained to Steve the problem and proposed a solution: blending ethane with propane. It would cost $12,000 to $14,000, and Steve simply said, “Okay, I’ll order it in the morning.”

The logistical hurdles were significant. The ethane had to be sourced from Canada, shipped to Korea, and cleared through customs. Dealing with Korean customs was complex, and Steve was opposed to bribery, but the process may have involved some—not something we were directly involved in.

Sitara Maruf: Just as the balloon was ready to launch, Steve, already in the capsule, opened the hatch and asked you to show him how to use the autopilot. What did you do—and what did you feel?

Bruce Comstock: <Laughs> That felt a little bit frustrating! But I climbed in and showed him. For this Pacific flight Steve had the “toy” analog autopilot.

Sitara Maruf: Then you came up with a better autopilot, which Steve called the “Comstock Autopilot?”

Bruce Comstock: Yes, before Steve’s next round-the-world flight attempt, I designed and built a good autopilot for Steve. This autopilot, which Steve immediately named the “Comstock Autopilot”, was based on a single board digital computer. It required some patience to operate. I had designed it to watch the human pilot fly the balloon first. Instead of directly using the burner valve, the balloon pilot would control the burner through a switch on the autopilot. The autopilot would then learn how much heating was necessary to maintain altitude.

When designing it, I wanted the autopilot to work with any balloon, regardless of its specifications, without needing to know anything specific about the balloon. The autopilot learned about the balloon by observing a human pilot for about a minute, although it could take longer—sometimes two minutes—depending on the flight conditions. It needed to see a sufficient amount of heating time to accurately determine the balloon’s parameters.

Once it had enough information, the autopilot would notify the pilot—via a flashing light and an audible alarm —that it had taken over. From that point, the autopilot managed the flying.

Sitara Maruf: Late in the flight over the Pacific, there was no communication from Steve for about eight hours until he sent a message saying “That’s Vancouver Island below me. I have made the Pacific. Cheers, Steve”. What caused the communication blackout?

Bruce Comstock: It’s our belief that he turned off the master switch to save electricity. That was strange because it shut off everything, including the transponder. He was running low on power and had a generator and some large lead-acid batteries, but I guess he was having trouble with the generator and didn’t want to risk using up all the electricity.

Turning off the master switch meant the automatic position reports also stopped. Every 30 minutes, his GPS position was supposed to be sent to the communication center in England. I was there when people started wringing their hands in despair. I told the guy in charge, “I’m not overly concerned—Steve has probably just turned off the master switch to save power.” And that’s exactly what had happened.

What’s incredible is that Bo Kemper, who had high-level contacts in Washington, called someone in the Defense Department. At the time, a U.S. fleet was conducting maneuvers near Steve’s location. Bo managed to get them to launch a plane from an aircraft carrier, and it found Steve and reported back.

Sitara Maruf: Let’s talk about Steve’s first solo round-the-world attempt. You were the launch director along with Nick Saum, and Steve also had another engineer, Andy Elson, from England. Steve launched from the Strato Bowl in South Dakota, but after flying about 100 miles over the Atlantic Ocean, a low-pressure system intensified unexpectedly. There was a snowstorm. The balloon blew back to Canada and ultimately crashed into the Bay of Fundy, and Steve was rescued by the Coast Guard.

Bruce Comstock: He didn’t exactly land in the Bay of Fundy, but he was flung back onto land after crashing down in the water. The balloon hit the water hard, and it ripped off the solar array and the generator, which were fragile. My comment at the time was that both the generator and the solar array were where they belonged—at the bottom of the Bay of Fundy!

Steve asked Nick and me to fly up to where the balloon had landed and manage getting it packed up and sent back to England. The balloon was pretty well destroyed and never flown again. When we got there, we were a little depressed about how the flight had turned out. The envelope itself had problems separate from the weather. Steve was lucky he got flung back onto land after crashing into the water.

Sitara Maruf: Was this the first time a solar array was used for electric power?

Bruce Comstock: I’m not sure, but [during preparations] when we got to the Strato Bowl, we found this big solar array—about five feet by eight feet—designed to hang beneath the capsule. It had an automatic rotator to keep it pointed at the sun, but all its weight hung on a tiny aluminum shaft in the rotator. It was ridiculous and doomed to failure. We found a machinist to make a stainless-steel part to replace it, which helped, but the whole thing was cumbersome and not a good idea.

This problem arose because we were not involved in the early decisions. The flight was doomed partly because the envelope wasn’t working properly, and partly because the electrical system was far too complicated. It had the solar panel, storage batteries, a generator, and a charge controller trying to keep everything working.

When I got to the town where we were recovering the envelope, the first thing I did was think about how to simplify things. I realized we could get rid of the solar panel, generator, and charge controller by just using good batteries. It wasn’t elegant to some people, but in my mind, it was.

We put Bo Kemper to work with his contacts in the Defense Department, and he found excellent batteries for us. They worked perfectly. They cost over $20,000 for the flight, and when they weren’t needed anymore, they were just discarded as ballast. It was simple: batteries, good wiring, and proper circuit breakers. And it worked, guaranteed.

On January 12, 1996, Bruce Comstock and Nick Saum launched Steve Fossett from St. Louis. Fossett flew halfway around the world in the complex 210,000-cubic-foot Rozière balloon, ultimately landing in India. He persevered through scattered thunderstorms and flew just far enough to set the longest distance and duration world records. “We apparently had figured out how to do this right,” recounted Comstock in his book A Life in the Air.

Sitara Maruf: Let’s take a step back. What sparked your passion for ballooning?

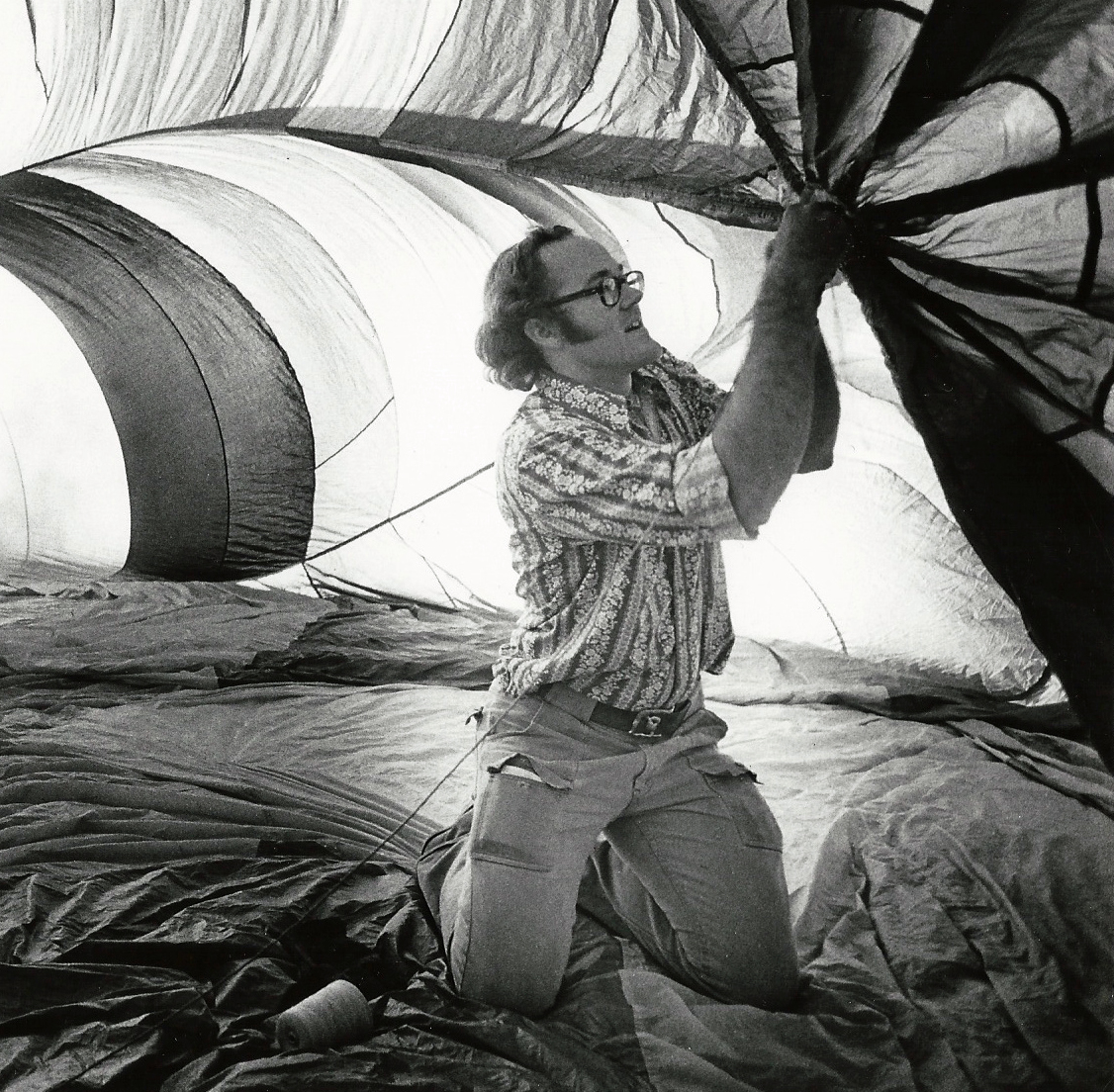

Bruce Comstock: It’s funny to think about now, but 55 years ago, ballooning was almost unheard of. I was mowing the lawn of my house during grad school at the University of Michigan when I saw a balloon fly by. I was stunned. My wife and I hopped into our Volkswagen and chased it. It was a tiny one-person chair balloon, flown by a plastic surgeon who lived nearby. We talked to the pilot. Balloons cost around $5,000 for a two-person model, which was completely out of reach for a grad student.

Sitara Maruf: So how did you eventually make it happen?

Bruce Comstock: A few years later, after I had a steady job, we took a $5 helicopter ride at a carnival. It was noisy, shaky, and uncomfortable, but as we flew over the woods, I kept thinking, “What would this be like in a balloon?”

When I got home, I pulled out information I’d saved about ballooning and contacted a company in South Dakota. They told me there was an instructor about an hour away from my home. That summer on weekends, I learned to fly. That’s how I earned my pilot’s license.

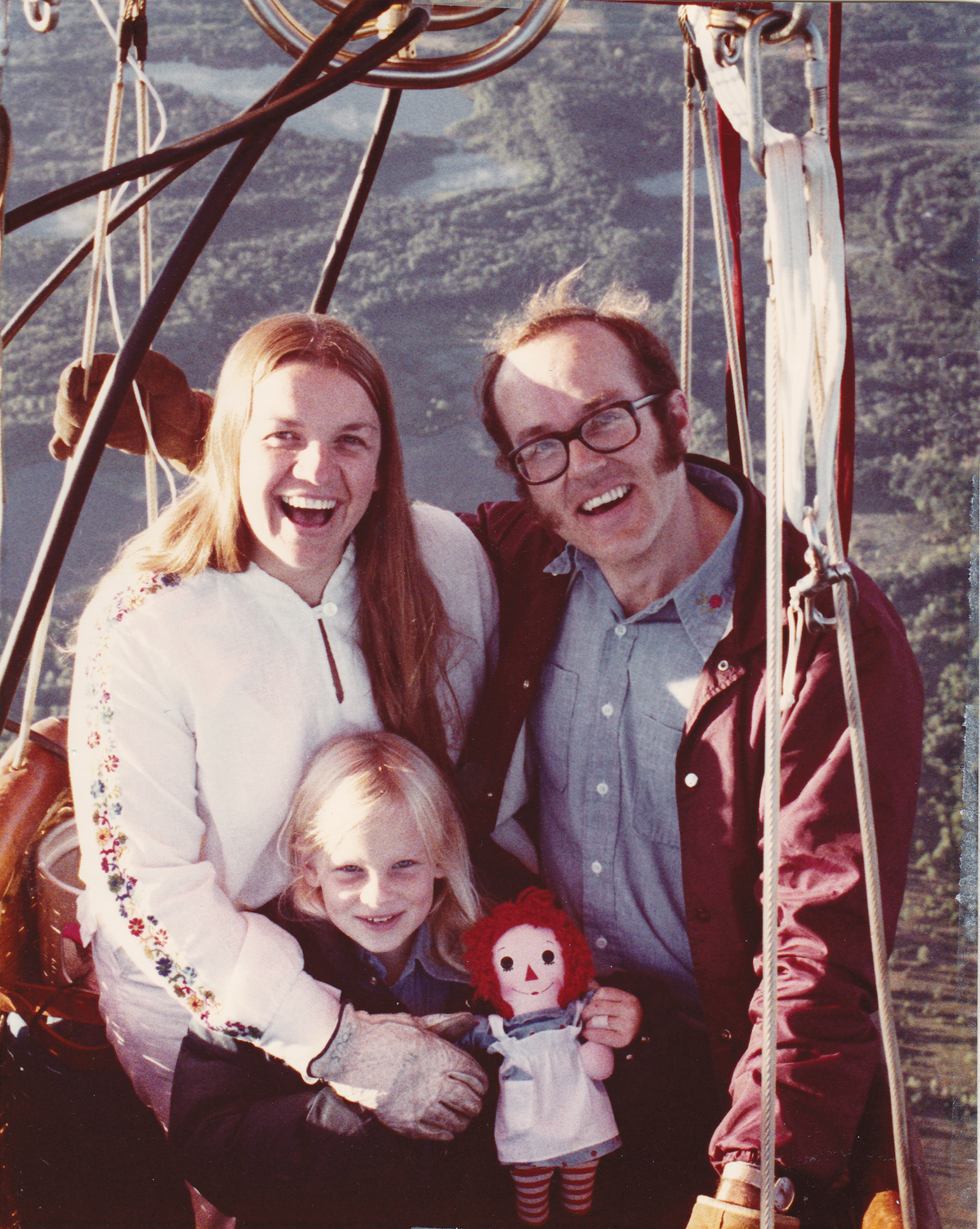

Sitara Maruf: You and Tucker, your wife at the time, discovered ballooning together. Did sharing that passion shape your journey?

Bruce Comstock: Oh, absolutely. Tucker is an amazing balloonist—she was inducted into the U.S. Ballooning Hall of Fame a couple of years ago. We did everything together, and I wouldn’t have accomplished even half of what I did without her.

I actually apologized to her years later, after we divorced. I worried I had dragged her into something that was my passion, not hers. She assured me she loved the journey as much as I did. Together, we complemented each other’s strengths and made ambitious decisions, like starting a balloon manufacturing business after I won the World Championship. When I think back now, especially about the decision to manufacture balloons, I sometimes wonder, What were we thinking? (laughs) The chances of succeeding were slim, but we just went for it.

Sitara Maruf: Over your career, how have you seen ballooning evolve in terms of technology and challenges?

Bruce Comstock: Balloons today are so much better than they were 50 years ago. I competed for about 23 years continuously, and by my last decade, the equipment had drastically improved.

For example, the balloon I learned on had a burner with a heat output of about 4 million BTUs per hour on a good day. Of that, about 1 million BTUs just kept the balloon in the air. In winter, with lower fuel pressure, it was even less! By contrast, the competition balloon I flew later in my career had a double burner capable of producing 52 million BTUs per hour. That’s a huge leap in power!

But learning on that older, underpowered balloon made me a better pilot because I had to pay close attention and solve problems without relying on power I didn’t have. It taught me to stay sharp and proactive.

Sitara Maruf: What about the balloon designs themselves?

Bruce Comstock: Everything about them has improved. The balloon I learned on had an aluminum gondola with a fiberglass floor and rigid metal sides. It wasn’t forgiving—on hard landings, I’d get bruises from banging against the big 20-gallon tanks on either side.

Today’s baskets are much more sophisticated. They’re built with flexible structural elements hidden inside, which absorb impact and reduce the risk of injury during landings. The fabrics are specifically designed and engineered for use in hot air balloons. There’s really no comparison.

Photo and all other images (unless noted) courtesy of Bruce Comstock.

Sitara Maruf: Are you still involved in lighter-than-air activities or flying?

Bruce Comstock: I haven’t flown much recently. A couple of years ago, my wife and I visited Ann Arbor and stopped by the Cameron factory. Andy and his wife had a balloon set up, and I asked if I could inflate it. I promised, “I won’t burn it!” (laughs) He agreed, and after a quick briefing on the burner—because they’ve evolved over the years—I inflated the balloon. Then Andy, Karen, and I took off, and I piloted the entire flight.

Before that, I had a balloon in Oregon for a while, but flying there was challenging. It’s all small mountain valleys where you can only fly in the morning, and you can’t go too far because the retrieval gets complicated once you leave the valley. I found it boring.

Few times, I flew in California’s Shasta Valley, which is a big, flat area. There’s no wind in the morning because cold air settles into the valley overnight. I calculated that for my four flights there, my average speed was about one mile per hour. You could practically crawl at that speed! And as I have said this many times, after flying at 100 miles per hour in a balloon, it’s hard to get excited about flying at one mile per hour.

Sitara Maruf: Is there anything you’d like to add?

Bruce Comstock: I feel incredibly fortunate and grateful that I stumbled into ballooning—or got sucked into it. That led to a truly fascinating life. Now I often say that when I visit a balloon museum, I feel like one of the artifacts! (laughs)

###